For most people. knowledge of hazardous plants is limited to the phrase, “leaves of three, leave them be.” However, despite widespread awareness of a few common culprits, many casual outdoor enthusiasts may still find themselves with an itchy souvenir following an encounter with an apparently innocent looking flower or shrub. Enter poison ivy! One of the most notorious causes of plant contact dermatitis in the United States.1

For most people. knowledge of hazardous plants is limited to the phrase, “leaves of three, leave them be.” However, despite widespread awareness of a few common culprits, many casual outdoor enthusiasts may still find themselves with an itchy souvenir following an encounter with an apparently innocent looking flower or shrub. Enter poison ivy! One of the most notorious causes of plant contact dermatitis in the United States.1

What is poison ivy?

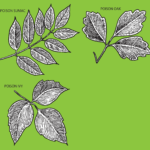

Poison ivy, along with poison oak and poison sumac, is a member of the Anacardiaceae family.2-4 Sap from the leaves, stems, roots, and berries of the Anacardiaceae family contains an oily resin called urushiol (u-ROO-she-ol), exposure to which can result in an intensely itchy and often blistery rash that can last for weeks, regardless of treatment. Each additional exposure to urushiol can cause increasingly severe skin reactions.2 This allergic reaction is called toxicodendron contact dermatitis (TCD).

Urushiol is sticky and can easily attach to your skin and clothing. Some common ways this oil can spread to your skin include brushing up against one of these plants, touching something that has the oil on it (e.g., clothing, pet’s fur, or gardening tools), or getting tiny pieces of these plants on your skin when someone uses physical force to eradicate the plant.4

It is estimated that 50 to 75 percent of the US adult population is clinically sensitive to poison ivy, oak, and/or sumac.2 In addition to being red and often extremely itchy, TCD can also cause swelling and blisters in affected areas of the skin.5,6 Most people who come into physical contact with these these plants will develop a rash within 12 to 72 hours that may last for several weeks.2,5 The amount of urushiol that gets on your skin will affect how severe the reaction is. For example, the portion of skin that comes into direct contact with the oily residue may develop a rash sooner and more intensely than other parts of the body that experience indirect exposure (e.g., from clothing that’s come into contact with the plants)2,4

A common misconception regarding TCD is that the rash is contagious…it is not. Because the rash tends to appear on additional parts of the body over a period of time, instead of all at once, it may seem like the rash is spreading on its own. But this may be because the plant oil is absorbed at different rates on different parts of exposed skin or previously unaffected skin is being exposed to the oil by way of contaminated objects (e.g., clothing) or other body parts (e.g., plant oil trapped under fingernails).3,5–7 As long as no oily residue from the plant remain on the skin, the rash cannot be spread to other parts of the body or to other people, either by direct contact with the rash or via scratching. The rash can only appear on parts of the body where the plant oil has touched the skin.6

Managing the Rash

Treatment and prevention therapies for TCD have not changed significantly over the years.9 There is no cure for the rash, and most treatment methods are focused on alleviating the symptoms. This can be done safely at home if the reaction is mild and on a small section of the skin.10 More severe symptoms may require the care of a physician or dermatologist.

Mild cases

- Take short, lukewarm baths. To ease the itch, take short, lukewarm baths in a colloidal oatmeal preparation, which you can buy at your local drugstore.10,11 You can also draw a bath and add one cup of baking soda to the running water. Taking short, cool showers may also help.

- Avoid the heat. Stay away from anything that heats up your skin, including hot showers or baths and direct sunlight. This can make itching worse.11

- Apply medications and/or skin protectants to the affected area. Calamine lotion and hydrocortisone cream can reduce itch.10,11 Applying topical over-the-counter skin protectants, such as zinc acetate, zinc carbonate, and zinc oxide, help dry the oozing and weeping of the blisters.3 Similarly, baking soda, colloidal oatmeal, and aluminum acetate can help relieve minor irritation and itching. Do not apply antihistamine to your skin, as doing so may worsen the rash and the itch.10

- Apply cool compresses or wet dressings. Cold compresses can help provide mild relief from itching and reduce inflammation.10,11 The cold temperature can also offer a temporary numbing effect. This is best done on smaller areas of the body, and can be administered for 30 minutes 3 to 4 times a day.12

Severe cases

If the rash shows signs of infection or does not begin to improve within 10 days, seek treatment from a doctor or dermatologist immediately, particularly if any of the following symptoms are present:

- The reaction is severe or widespread.

- You inhaled the smoke from burning poison ivy and are having difficulty breathing.

- Your skin continues to swell.

- The rash affects your eyes, mouth, or genitals.

- Blisters are oozing pus.

- You develop a fever greater than 100˚F (37.8˚C).

Identifying Poison Ivy, Removing the Plant, and Preventing Exposure

Poison ivy can be found throughout the US, with the exceptions of Alaska, Hawaii, and parts of the West Coast. Contact with the plant can result in a rash regardless of time of year. These plants can be found in forests, fields, wetlands, and along streams, road sides, and even in urban environments, such as, parks, gardens, and backyards.2,8

Poison ivy can grow as a vine or small shrub, trailing along the ground, climbing on low plants or up trees or poles. Each leaf has three glossy leaflets, with smooth or toothed edges.3 Leaves are a reddish color in spring, green in summer, and yellow, orange, or red in fall, and the plant can have greenish-white flowers and whitish-yellow berries.

The best way to prevent TCD is by removing its source.13 If you do spot poison ivy, you can eradicate it or any lingering shoots or seedlings with white vinegar.14 Other ways to prevent TCD include:

- Immediately rinsing your skin with soapy water after exposure. If you rinse your skin immediately after touching poison ivy, you may be able to rinse off most of the oil. If not washed off, the oil can spread from person to person and to other areas of your body.9

- Washing your clothing. Thoroughly wash the clothes you were wearing in hot water when you came into contact with the plant. Urushiol can stick to clothing, and if it touches your skin, it can cause another rash.3

- Being wary of urushiol. If you’re working in an area where there may be poison ivy, wash your garden tools and gloves regularly. Keep exposed skin covered by wearing long sleeves, long pants tucked into boots, and impermeable gloves.3

- Using plastic bags to remove the poison ivy plants. When removing poison ivy, cover your hands in plastic bags, replacing them as you pull each plant from the ground. Notably, dying and even dead poison ivy plants contain urushiol.14

REFERENCES

1. Margosian E. May 2021. More than just poison ivy. DermWorld website. http://digitaleditions.walsworthprintgroup.com/publication/?i=497362&articlen_id=3090871&view =articleBrowser&ver=html5. Accessed 5 May 2021.

2. Monroe J. Toxicodendron contact dermatitis: a case report and brief review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020;13(9 Suppl 1):S29-S34.

3. FDA. Updated 2 Feb 2021. Outsmarting Poison Ivy and Other Poisonous Plants. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/outsmarting-poison-ivy-and-other-poisonous-plants. Accessed 6 May 2021.

4. Sparks D. Updated 29 Jun 2020. Itchy, irritating poison ivy rash. Mayo Clinic website. https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/itchy-irritating-poison-ivy-rash/. Accessed 10 May 2021.

5. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac: when does the rash appear? AAD website. https://www.aad.org/public/everyday-care/itchy-skin/poison-ivy/rash-appear. Accessed 5 May 2021.

6. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac: what does the rash look like? AAD website. https://www.aad.org/public/everyday-care/itchy-skin/poison-ivy/what-rash-looks-like. Accessed 5 May 2021.

7. Walsh E, Allmann Updyke E. 29 Dec 2020. Ep 63 Poison Ivy: it’s just us. This Podcast Will Kill You website. http://thispodcastwillkillyou.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/TPWKY-Episode-63-Poison-Ivy.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2021.

8. NIOSH. Updated 1 Jun 2018. Poisonous plants. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health website. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/plants/geographic.html. Accessed 10 May 2021.

9. Kim Y, Flamm A, ElSohly MA, et al. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac dermatitis: what is known and what is new? Dermatitis. 2019;30(3):183-190.

10. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac: how to treat the rash. AAD website. https://www.aad.org/public/everyday-care/itchy-skin/poison-ivy/treat-rash. Accessed 5 May 2021.

11. Liu B, Jordt SE. Cooling the Itch via TRPM8. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(6):1254-1256.

12. Contact Dermatitis. Fairview Health Services website. https://www.fairview.org/sitecore/content/Fairview/Home/Patient-Education/Articles/English/c/o/n/t/a/Contact_Dermatitis_115897en. Accessed 24 May 2021.

13. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Poison ivy, oak, and sumac: how can I prevent a rash? AAD website. https://www.aad.org/public/everyday-care/itchy-skin/poison-ivy/prevent-rash. Accessed 5 May 2021.

14. Schottelkotte D. Updated 7 Jun 2019. Mom Knows Best: Avoid Poisonous Plants. MercyHealth website. https://blog.mercy.com/poisonous-plants/. Accessed 24 May 2021.