Tendons are strong, flexible cords of tissues that connect muscles to bones. When we contract our muscles, tendons pull the attached bone, and they can absorb some impact from muscle movement.1,2 Ligaments are bands of tissue that connect and stabilize bones, joints, and organs. Ligaments are responsible for preventing the dislocation of bones and twisting of joints.1,3 Cartilage is a flexible connective tissue that surrounds the ends of bones and cushions joints. Cartilage acts as a shock absorber to reduce stress on bones and joints, reduces friction between bones, and supports the structure of joints.4 All three of these tissues are crucial components for the movement and structure of the body.

Tendons are strong, flexible cords of tissues that connect muscles to bones. When we contract our muscles, tendons pull the attached bone, and they can absorb some impact from muscle movement.1,2 Ligaments are bands of tissue that connect and stabilize bones, joints, and organs. Ligaments are responsible for preventing the dislocation of bones and twisting of joints.1,3 Cartilage is a flexible connective tissue that surrounds the ends of bones and cushions joints. Cartilage acts as a shock absorber to reduce stress on bones and joints, reduces friction between bones, and supports the structure of joints.4 All three of these tissues are crucial components for the movement and structure of the body.

Tendons

Tendons are composed of collagen fibers arranged in bundles. They are stiffer than muscles, have greater tensile strength, and can withstand heavy loads with minimal deformations. For example, the flexor tendons in the foot can support over eight times one’s body weight. Tendons vary in size based on their attached muscles. Typically, wide and short tendons are attached to muscles that generate large amounts of force, having greater tensile strength than thinner and longer tendons, which are attached to muscles responsible for more delicate and less forceful movements. Some tendons are surrounded by tendon sheaths that are responsible for producing synovial fluid, which lubricates the area and allows the tendon to move smoothly. Tendons attach to muscles and bones at the muscle-tendon junction and osteo-tendinous junction, respectively.2,5

With age, tendons weaken and become more susceptible to injury. Loss of estrogen in female individuals loosens tendons, thus making them more susceptible to injury and inflammation.5

Strains, one of the most common tendon injuries, occur when a tendon is overstretched, torn, or twisted, typically due to repetitive movements or physical activity. Strains often occur in the arms, legs, feet, and back.1,2 Another common tendon injury is tendinitis, which happens as a result of inflammation of the tendon. Overuse, repetitive movements, and aging can cause tendinitis. Common areas affected by tendinitis include rotator cuff, elbow, wrist, knee, and ankle.2,6 A combination of tendinitis and inflammation of the tendon sheath is called tenosynovitis, commonly affecting the fingers.2 These issues of the tendon can be treated with rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE), as well as anti-inflammatory medications. In certain cases, tendinitis and tenosynovitis may require surgical care.1,2,6

Ligaments

Similar to tendons, ligaments are made of collagen bundles. These strong bands of flexible tissue connect to most bones in the body, limiting the amount of movement between bones.3,7 Ligaments can stabilize organs as well. For instance, ligaments connect the liver, stomach, and intestine and hold them in place, and they stabilize the uterus in the pelvis.3

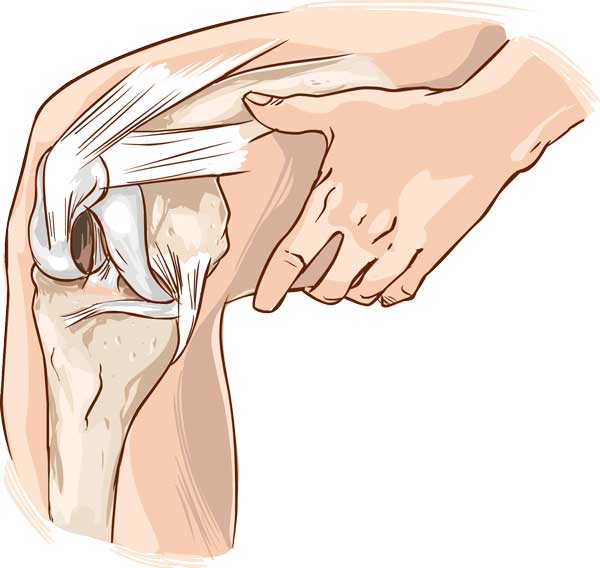

Ligament sprains occur when the tissue is overstretched or torn. Sprains commonly occur in the wrist, ankle, or knee, and are often caused by sudden impacts, falls, or twists. Pain, swelling, difficulty bearing weight, and looseness in the affected area are symptoms of sprains.1,3,7 Ligament sprains are divided into three grades. Grade 1 sprains are mild, typically healing within six weeks. These can be treated with RICE and anti-inflammatory medications. Grade 2 sprains involve a partial tear, with increased difficulty bearing weight and using the affected body part compared to a Grade 1 sprain. Using a brace or another supportive device is often recommended to avoid stretching the ligament. Grade 2 sprains often take 6 to 12 weeks to heal. Grade 3 sprains involve complete tear or rupture, accompanied by severe pain, bruising, and swelling. Avoiding stress from weight bearing is crucial for proper healing, and in some cases, surgery is necessary to repair the ligament. These injuries can take several months, or even a year or more, to fully heal.3,7

Cartilage

Cartilage is a flexible, nonvascular connective tissue composed of collagen and elastic fibers that comes in three forms. The most common type, hyaline cartilage, lines joints and the ends of bones. Its slippery, smooth surface allows for frictionless movement and prevents bones from rubbing against each other. Hyaline cartilage is located in the nasal passages, between the ribs and sternum, and at the ends of bones that form joints. Fibrocartilage is the toughest and least flexible type, and it provides support and rigidity in the body. Fibrocartilage can be found between spinal vertebrae, in the knee joint, and at the junction where tendons attach to bones. The most flexible type of cartilage is elastic cartilage. This cartilage provide support and maintains shape in areas such as the external ears, Eustachian tubes, and larynx.4,8

Osteoarthritis involves the breakdown of cartilage in the joints, leading to pain and inflammation. Herniated disks occur when cartilage between the vertebrae is torn or punctured.4,8 Injuries, such as meniscal tears or a separated shoulder, can tear or damage cartilage in the joints.4 Additionally, forceful or small and repetitive impacts and twisting the joint when it is bearing weight can damage cartilage. Cartilage injuries occur most frequently in the knee, but other common areas of injury include the shoulder, ankle, and hip.9

Nutrition for Health Tendons, Ligaments, and Cartilage

Vitamin C contributes to collagen synthesis, with vitamin C deficiency leading to collagen loss;10–12 as tendons and ligaments are composed of cartilage, sufficient vitamin C consumption is crucial. Supplementing vitamin C with gelatin10,11,13 or collagen10,11 has potential to treat tendon and ligament injuries, though further research is needed to verify this finding. Citrus fruits, red bell peppers, strawberries, broccoli, and kiwis are good sources of vitamin C.11,12

Emerging evidence suggests that the intake of hydrolized collagen supplements, in combination with other therapies, might reduce pain related to tendon injuries.11,14,15 However, more high-quality studies are needed to confirm these claims.

Vitamin D and K deficiencies are associated with cartilage damage and osteoarthritis. Foods high in vitamin K include broccoli, Brussels sprouts, and leafy greens.16,17 Additionally, certain oils and fats can contain small amounts of vitamin K, and eating these with the vegetables high in vitamin K can increase the vitamin’s bioavailability, since it is a fat soluble vitamin.16 Although the main source of vitamin D is through sun exposure, fatty fish, mushrooms, egg yolks, and fortified foods and beverages.16,17

Saturated fatty acid intake should be limited, as high amounts of SFAs can lead to cartilage degeneration.18 Furthermore, omega-6 fatty acid consumption can increase the risk of inflammation16 and osteoarthritis.18 Safflower and sunflower oils have high levels of omega-6 fatty acids.18 Conversely, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (e.g., docosahexaenoic acid [DHA], eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA]) intake might protect against cartilage damage and osteoarthritis.16,18 Sources high in omega-3 fatty acids include cod liver oil, mackerel, salmon, sardines, herring, kippers, tuna, and other cold-water fish.16,17

Sources

- Christiano D. What’s the difference between ligaments and tendons? Healthline. Updated 18 Sep 2018. https://www.healthline.com/health/ligament-vs-tendon#function. Accessed 4 Jan 2023.

- Cleveland Clinic. Tendon. Reviewed 10 Aug 2021. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21738-tendon. Accessed 4 Jan 2023.

- Cleveland Clinic. Ligament. Reviewed 6 Jul 2021. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/21604-ligament. Accessed 4 Jan 2023.

- Cleveland Clinic. Cartilage. Reviewed 24 May 2022. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23173-cartilage. Accessed 4 Jan 2023.

- Bordoni B, Varacallo M. Anatomy, tendons. Updated 18 Jul 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022/

- Hospital for Special Surgery. Tendinitis/tendinitis. https://www.hss.edu/condition-list_tendonitis.asp. Accessed 4 Jan 2023.

- Physiopedia. Ligament. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Ligament. Accessed 4 Jan 2023.

- Physiopedia. Cartilage. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Cartilage. Accessed 4 Jan 2023.

- Yale Medicine. Cartilage injury and repair. https://www.yalemedicine.org/conditions/cartilage-injury-and-repair. Accessed 4 Jan 2023.

- Noriega-González DC, Drobnic F, Caballero-García A, et al. Effect of vitamin C on tendinopathy recovery: a scoping review. Nutrients. 2022;14(13):2663.

- Turnagöl HH, Koşar ŞN, Güzel Y, et al. Nutritional considerations for injury prevention and recovery in combat sports. Nutrients. 2022;14(1):53.

- Tremblay S. Nutrients Needed for Tendons on Ligaments. SFGate. Updated 6 Dec 2018. https://healthyeating.sfgate.com/best-indoor-cycling-bikes-13771759.html. Accessed 9 Jan 2023.

- Baar K. Stress relaxation and targeted nutrition to treat patellar tendinopathy. Int J Sport Nutr. 2019;29(4):453–457.

- Praet SFE, Purdam CR, Welvaert M, et al. Oral supplementation of specific collagen peptides combined with calf-strengthening exercises enhances function and reduces pain in Achilles tendinopathy patients. Nutrients. 2019;11(1):76.

- Qiu F, Li J, Legerlotz K. Does additional dietary supplementation improve physiotherapeutic treatment outcome in tendinopathy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11(6):1666.

- Thomas S, Browne H, Mobasheri A, Rayman MP. What is the evidence for a role for diet and nutrition in osteoarthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(Suppl 4):iv61–iv74.

- Andwele M. Eat right for your type of arthritis. Arthritis Foundation. 18 Jun 2021. https://www.arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/nutrition/healthy-eating/eat-right-for-your-type-of-arthritis. Accessed 9 Jan 2023.

- Mustonen A-M, Käkelä R, Joukainen A, et al. Synovial fluid fatty acid profiles are differently altered by inflammatory joint pathologies in the shoulder and knee joints. Biology. 2021;10(5):401.