By Sarabeth Lowe, MPH

Ms. Lowe is a Communication Specialist at the University of Delaware Disaster Research Center.

Welcome to the fourth edition of Health Literacy Highlights, a column that explores topics related to finding, understanding, and utilizing health information. This column is meant to empower you with the skills you need to apply what you already know and use it to maintain and protect your overall health and wellbeing. In this installment of Health Literacy Highlights, I focus on the social determinants of health (SDoH) and their impact on public health.

Health is more than just the absence of disease or injury.1–3 It’s also more than just a matter of your genes and choices. There are a myriad of variables that directly affect our wellbeing, beginning with where we live, work, and play. Upstream factors—the fundamental social, cultural, and political structures and systems in place—are the driving forces behind the health inequities we see every day.4 Efforts to improve health in the United States (US) have traditionally looked to the healthcare system to alleviate these disparities, but this approach often misses the forest for the trees. It’s also largely ineffective. Research and history show that this approach is not working.5–7 Despite being widely recognized and documented for many years, disparities in health and healthcare have persisted and, in some cases, widened over time in the US.8–11

Improving health outcomes and achieving health equity require broader approaches that address social, economic, and environmental factors. This has led many practitioners, researchers, and experts to advocate for a strategy that directly addresses the causes—not the symptoms—of these disparities. In other words, they are calling for going back to basics: social determinants of health (SDoH).

What Are SDoH?

SDoH are the evolving societal systems, their components, and the resources and hazards for health systems that social systems control, distribute, allocate, and withhold that, in turn, cause health consequences.12 SDoH are also described as:13–17

Nonmedical or nonbiological factors that influence health outcomes, risks, quality of life, and longevity; for example, race itself isn’t a SDoH, but racism and its social manifestations, like a ZIP code’s history of school segregation or redlining, are.18

Conditions and environments in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age.

Wider forces and systems that shape the conditions of daily life.

Upstream social and economic factors that dictate the health and disease of individuals and populations.

In short, SDoH are the “causes behind the causes” of health disparities.13 They describe a simple idea: a person’s health is influenced not just by their behavior or actions, but also by social factors. These factors include a variety of personal, social, and environmental conditions and structures, including economic policies, development agendas, social norms, social policies, climate change, and political structures.14 Notably, many SDoH are out of a person’s control.18

The 5 Domains of SDoH

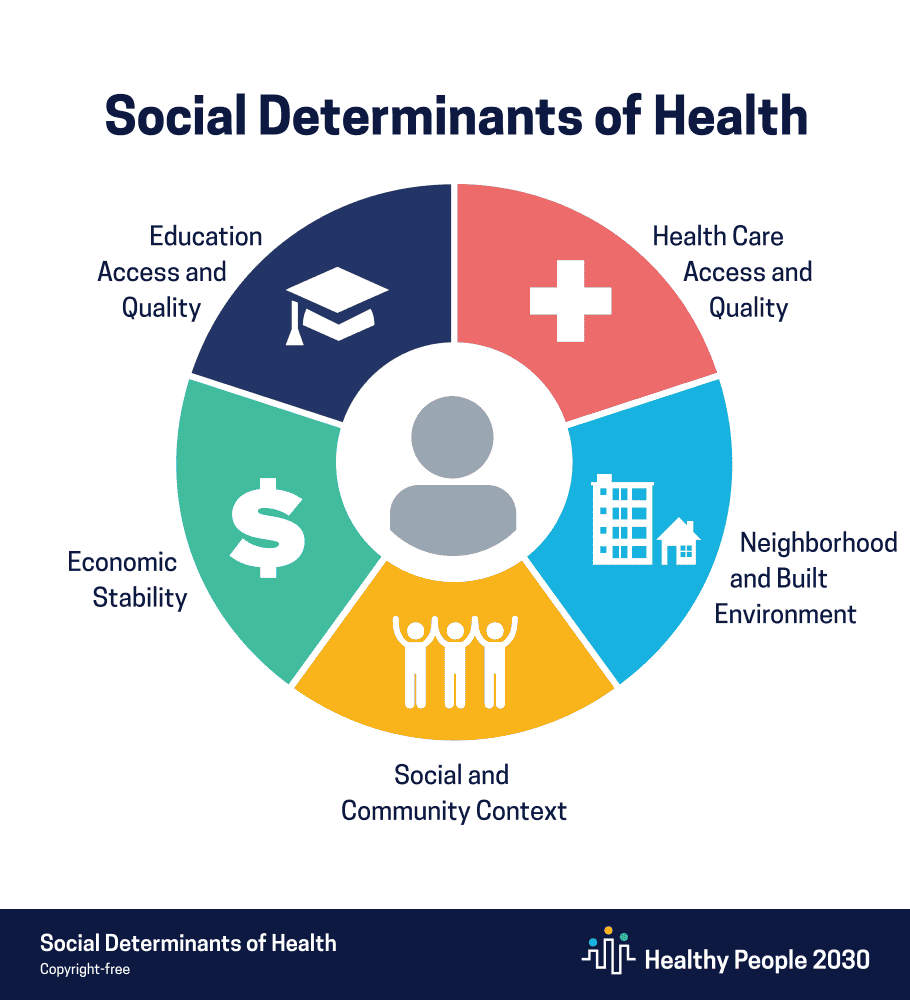

SDoH are one of three priority areas—along with health equity and health literacy—for the fifth and current edition of Healthy People, a federal and decadal initiative that sets goals and objectives to improve the health and wellbeing of people in the US.14,15,17 One of Healthy People 2030’s five overarching goals is specifically related to SDoH: “Create social, physical, and economic environments that promote attaining the full potential for health and wellbeing for all.”19–21

The US Department of Health and Human Services had grouped SDoH into five key areas.

Economic stability. This domain refers to the connection between a person’s financial status and their health. It encompasses many factors, including income and expenses, social safety net programs (eg, welfare and food stamps), job stability, employment benefits, socioeconomic status, and the general cost of living.17,18,22,23 All of these factors impact a person’s health. Extensive evidence shows that financially disadvantaged individuals have poorer health outcomes than their wealthier counterparts.24–27 For example, higher wealth and income can lead to better health by providing material and employment benefits that promote good health: safe homes and neighborhoods, paid time off work, health insurance, transportation, education, and more. Having a higher socioeconomic status can also reduce the persistent psychosocial stress associated with not having these material resources, which can lead to chronic disease.24,28,29

Education access and quality. This domain refers to a person’s access to and quality of education, and how well it supports their individual learning needs, including those related to how the brain works.18 It encompasses several factors, such as teacher training, geographic location, school facilities (eg, labs, playgrounds, safe classrooms and buildings), curriculum quality and relevance, material resources, educational infrastructure (eg, leadership, policies, and systems), and access to specialized student programs.30,31 Research shows that education and health are intrinsically linked.32 Education is strongly associated with life expectancy, morbidity, and health behaviors.33 It also increases financial security, stable employment, and social success, playing a critical role in lifting people out of poverty and reducing socioeconomic and political inequalities.32,34,35

Healthcare access and quality. This domain refers to a person’s access to and the quality of health-promoting care and resources, and how well it can meet their physical and mental health needs.18 It encompasses several factors, including affordable and easily attainable care, health literacy, health insurance, regularly visiting a primary care doctor, seeing doctors for illness and injuries, receiving mental and behavioral health services, and responding to medical emergencies.36–38 A number of social and economic issues, such as cost and coverage of care, limited access to providers that accept Medicaid, a shrinking healthcare workforce, and fewer medical services and clinicians in rural areas, take a toll on people’s long-term health and contribute to poor wellbeing outcomes.39–44

Neighborhood and built environment. This domain refers to the place someone lives, including its physical, environmental, and societal conditions and its impact on public health and wellbeing.45–47 These factors are related to your ZIP code and the specific community resources that support your health and safety, such as equitable, affordable, and high-quality housing, sidewalks, low rates of crime and violence, schools, workplaces, places of worship, grocery stores, transportation infrastructure, and green spaces.18,48 This SDoH also encompasses climate change. Each of these elements affects the “availability, accessibility, affordability, placement, and condition of the goods and services” that enable communities to live and thrive.46

Social and community context. This domain concerns social capital, which is the value or social currency from relationships and connections that allow people and communities to function and thrive.49–51 It refers to the impacts of relationships and the settings where people live, work, and interact with others; it also includes the interactions between people and connections with larger social, cultural, and other institutions.18,49–53 People face many challenges that they cannot control, such as unsafe neighborhoods, discrimination, or financial strains.49 Each of these can adversely affect public and personal health, but higher levels of social capital can help reduce some of these negative impacts. For example, civic participation, such as actively engaging in a local hobby group or membership in a faith-based organization, can help build relationships and improve physical and mental health outcomes.54,55

It’s important to remember that SDoH do not exist in isolation.18 They are tightly connected, and all of them interact, influence, and, sometimes, exacerbate each other. For example, climate change can affect nearly every aspect of your life, including food and water availability, housing affordability, air quality, and more frequent and intense natural hazards.56

Bottom line

The significance of the SDoH in public health cannot be understated. They are not just related to your health—they can actually determine it. The impacts of these upstream factors are pervasive and deeply entrenched in our society, creating inequities in access to a range of social and economic benefits, such as housing, education, wealth, and employment, that put people at higher risk of poor health.14–16 Understanding the SDoH is a critical and urgent challenge because addressing them moves us closer toward achieving health equity, a state in which every person has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health.14,57 Everybody wins when this goal is slated at the forefront of public health endeavors.

Sources

- Schramme T. Health as complete well-being: the WHO definition and beyond. Public Health Ethics. 2023;16(3):210–218.

- Constitution of the World Health Organization. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1946;36(11):1315–1323.

- International Declaration of Health Rights. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. 2023. Accessed 10 Dec 2025. https://publichealth.jhu.edu/about/at-a-glance/mission-vision-and-values/international-declaration-of-health-rights

- Ray R, Lantz PM, Williams D. Upstream policy changes to improve population health and health equity: a priority agenda. Milbank Q. 2023;101(S1):20–35.

- Artiga S, Hinton E. Beyond health care: the role of social determinants in promoting health and health equity. KFF. 10 May 2018. Accessed 1 Dec 2025. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245.

- Lee H, Kim D, Lee S, Fawcett J. The concepts of health inequality, disparities and equity in the era of population health. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;56:151367.

- Artiga S. Health disparities are a symptom of broader social and economic inequities. KFF. 1 Jun 2020. Accessed 1 Dec 2025. https://www.kff.org/covid-19/health-disparities-symptom-broader-social-economic-inequities/

- Ndugga N, Pillai D, Artiga S. Disparities in health and health care: 5 key questions and answers. KFF. 14 Aug 2024. Accessed 1 Dec 2025. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/disparities-in-health-and-health-care-5-key-question-and-answers/

- Levins H. Despite broad efforts, US health equity gap continues to grow. The University of Pennsylvania Leonard David Institute of Health Economics. 8 Apr 2024. Accessed 1 Dec 2025. https://ldi.upenn.edu/our-work/research-updates/despite-broad-efforts-u-s-health-equity-gap-continues-to-grow/

- Dwyer-Lindgren L, Baumann MM, Li Z, et al. Ten Americas: a systematic analysis of life expectancy disparities in the USA. Lancet. 2024;404(10469)2299–2313.

- Hahn RA. What is a social determinant of health? Back to basics. J Public Health Res. 2021;10(4):2324.

- Demaio S. What are ‘social determinants of health’? The Conversation. 20 Nov 2012. Accessed 9 Dec 2025. https://theconversation.com/what-are-social-determinants-of-health-10864

- Social determinants of health (SDOH). US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated 17 Jan 2024. Accessed 9 Dec 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/about/priorities/why-is-addressing-sdoh-important.html

- Social determinants of health (SDOH). US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated 15 May 2024. Accessed 9 Dec 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/about/social-determinants-of-health.html

- Social determinants of health. World Health Organization. 6 May 2025. Accessed 1 Dec 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/social-determinants-of-health

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Informing the Selection of Leading Health Indicators for Healthy People 2030. Criteria for selecting the leading health indicators for Healthy People 2030. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). 6 Aug 2019. Appendix E, Healthy People 2030 framework. Accessed 9 Dec 2025.

- Social determinants of health. Cleveland Clinic. Reviewed 8 May 2024. Accessed 1 Dec 2025. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/social-determinants-of-health

- Social determinants of health. US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed 9 Dec 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

- Healthy People 2030 questions & answers. US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Updated 18 Nov 2025. Accessed 9 Dec 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/our-work/national-health-initiatives/healthy-people/healthy-people-2030/questions-answers

- Healthy People 2030 framework. US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed 9 Dec 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/about/healthy-people-2030-framework

- Economic stability. US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed 11 Dec 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/economic-stability

- Economic stability. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated 27 Mar 2023. Accessed 11 Dec 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/prepyourhealth/discussionguides/economicstability.htm

- White N, Packard K, Kalkowski J, et al. Improving health through action on economic stability: results of the Finances First randomized controlled trial of financial education and coaching in single mothers of low-income. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2022;17(3):424–436.

- Pickett KE, Wilkinson RG. Income inequality and health: a causal review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:316–326.

- Ailshire JA, Herrera CA, Choi E, et al. Cross-national differences in wealth inequality in health services and caregiving used near the end of life. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;58:101911.

- Kondo N, Sembajwe G, Kawachi I, et al. Income inequality, mortality, and self rated health: meta-analysis of multilevel studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b4471.

- Larzelere MM, Jones GN. Stress and health. Prim Care. 2008;35(4):839–856.

- Juster RP, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35(1):2–16.

- Education access & quality. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated 27 Mar 2023. Accessed 11 Dec 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/prepyourhealth/discussionguides/education.ht

- Education access and quality. US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed 11 Dec 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/education-access-and-quality

- The Lancet Public Health. Education: a neglected social determinant of health. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(7):e361.

- Masters RK, Hummer RA, Powers DA. Educational differences in US adult mortality: a cohort perspective. Am Sociol Rev. 2012;77(4):548-572.

- Zajacova A, Lawrence EM. The relationship between education and health: reducing disparities through a contextual approach. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:273–289.

- Panyi AF, Whitacre BE, Young A. The shifting relationship between educational attainment and poverty: analysis of seven deep southern states. Ann Reg Sci. 2025;74(1):16.

- Health care access and quality. US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed 11 Dec 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/topic/health-care-access-and-quality

- Health care access & quality. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated 27 Mar 2023. Accessed 11 Dec 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/prepyourhealth/discussionguides/healthcare.htm

- Social determinants of health: health care access and quality. Association of Clinicians for the Underserved. Feb 2024. Accessed 11 Dec 2025. https://clinicians.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Social-Determinants-of-Health-Health-Care-Access-and-Quality_Exec-Summary_Final-508.pdf

- Health-care access and quality. Child Welfare Information Gateway. Accessed 11 Dec 2025. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/social-determinants-health/health-care-access-and-quality/?top=315

- The state of healthcare workforce shortages: challenges, causes, and solutions. TNAA. 29 Aug 2025. Accessed 1 Dec 2025. https://tnaa.com/blog/the-state-of-healthcare-workforce-shortages-challenges-causes-and-solutions

- Health care workforce: key issues, challenges, and the path forward. US Department of Health and Human Services. 22 Oct 2024. Accessed 11 Dec 2025. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/

82c3ee75ef9c2a49fa6

304b3812a4855/aspe-workforce.pdf - Coombs NC, Campbell DG, Caringi J. A qualitative study of rural healthcare providers’ views of social, cultural, and programmatic barriers to healthcare access. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):438.

- Horstman C, Shah A. The state of rural primary care in the United States. The Commonwealth Fund. 17 Nov 2025. Accessed 11 Dec 2025. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2025/nov/state-rural-primary-care-united-states

- Ludomirsky AB, Schpero WL, Wallace J, et al. In Medicaid managed care networks, care is highly concentrated among a small percentage of physicians. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(5):760–768.

- Neighborhood and built environment. US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed 12 Dec 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/topic/neighborhood-and-built-environment

- Neighborhood and built environment. Child Welfare Information Gateway. Accessed 12 Dec 2025. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/social-determinants-health/neighborhood-and-built-environment/?top=317

- Neighborhood & built environment. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated 27 Mar 2023. Accessed 12 Dec 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/prepyourhealth/discussionguides/neighborhood.htm

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on the Review of Federal Policies that Contribute to Racial and Ethnic Health Inequities; Geller AB, Polsky DE, Burke SP, es. Federal Policy to Advance Racial, Ethnic, and Tribal Health Equity. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2023 Jul 27. 6, Neighborhood and built environment. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK596398/

- Social and community context. US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed 12 Dec 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/topic/social-and-community-context

- Eriksson M. Social capital and health–implications for health promotion. Glob Health Action. 2011;4:5611.

- Linde S, Egede LE. Community social capital and population health outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(8):e2331087.

- Social and community context. Child Welfare Information Gateway. Accessed 1 Dec 2025. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/social-determinants-health/social-and-community-context/?top=320

- Social & community context. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed 12 Dec 2025. Updated 27 Mar 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/prepyourhealth/discussionguides/community.htm

- Civic participation. US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Accessed 1 Dec 2025. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/civic-participation

- Dubowitz T, Nelson C, Weilant S, et al. Factors related to health civic engagement: results from the 2018 National Survey of Health Attitudes to understand progress towards a culture of health. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):635.

- Ragavan MI, Marcil LE, Garg A. Climate change as a social determinant of health. Pediatrics. 2020;145(5):e20193169.

- Achieving health equity. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Accessed 12 Dec 2025. https://www.rwjf.org/en/our-vision/focus-areas/Features/achieving-health-equity.html