Weight training for strength versus muscle growth

Lifting weights in a weight room or home gym is a great way to improve multiple facets of physical and mental health. A wonderful aspect

Lifting weights in a weight room or home gym is a great way to improve multiple facets of physical and mental health. A wonderful aspect

Creatine is a compound that is derived from the amino acids arginine, glycine, and methionine.1 The body needs 1 to 3g of creatine per day

Foam rolling is a form of self-myofascial release therapy wherein you roll over parts of the body (e.g., calves, thighs, upper back) using a foam

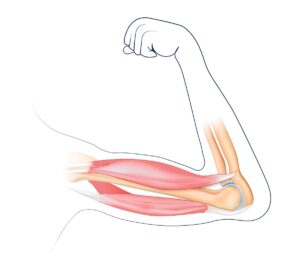

Sarcopenia is a progressive disorder characterized by low muscle strength, quality, and quantity. Low muscle strength indicates probable sarcopenia, and low muscle quality and quantity

Coffee is a staple of many breakfast routines, thanks to the energy boost it provides. One 8oz cup typically contains 95mg of caffeine. The Dietary

Cell-cultivated meat, also known as cultured meat, lab-grown meat, and in vitro meat, is a meat alternative created by harvesting cells from an animal, such

Get free recipes, tips on healthy living, and the latest health news

Get unlimited access to content plus receive 6 eye-appealing, information-packed print issues of NHR delivered to your mailbox.

info@matrixmedcom.com

866.325.9907 (toll-free, US) or 484.266.0702

Matrix Medical Communications

1595 Paoli Pike

Suite 201

West Chester, PA 19380

© 2023 Matrix Medical Communications